Dismantling problematic science stereotypes using selfies

LSU College of Science's Dr. Paige Brown Jarreau and LSU Experimental host Dr. Becky Carmichael, along with

Lance Porter from the LSU Manship School of Mass Communication, Imogene Cancellare from the University of Delaware, Dr. Samantha Yammine from the University of Toronto, and Daniel Toker from the University of California Berkeley, explored the role of science self portraits play in addressing problematic stereotypes.

LSU College of Science's Dr. Paige Brown Jarreau and LSU Experimental host Dr. Becky Carmichael, along with

Lance Porter from the LSU Manship School of Mass Communication, Imogene Cancellare from the University of Delaware, Dr. Samantha Yammine from the University of Toronto, and Daniel Toker from the University of California Berkeley, explored the role of science self portraits play in addressing problematic stereotypes.

The project was crowdfunded through Experiment.com and launched the #ScientistsWhoSelfie hashtag. The hashtag has been used over 14k times on Instagram and formed a community of scientists and science enthusiasts sharing discoveries!

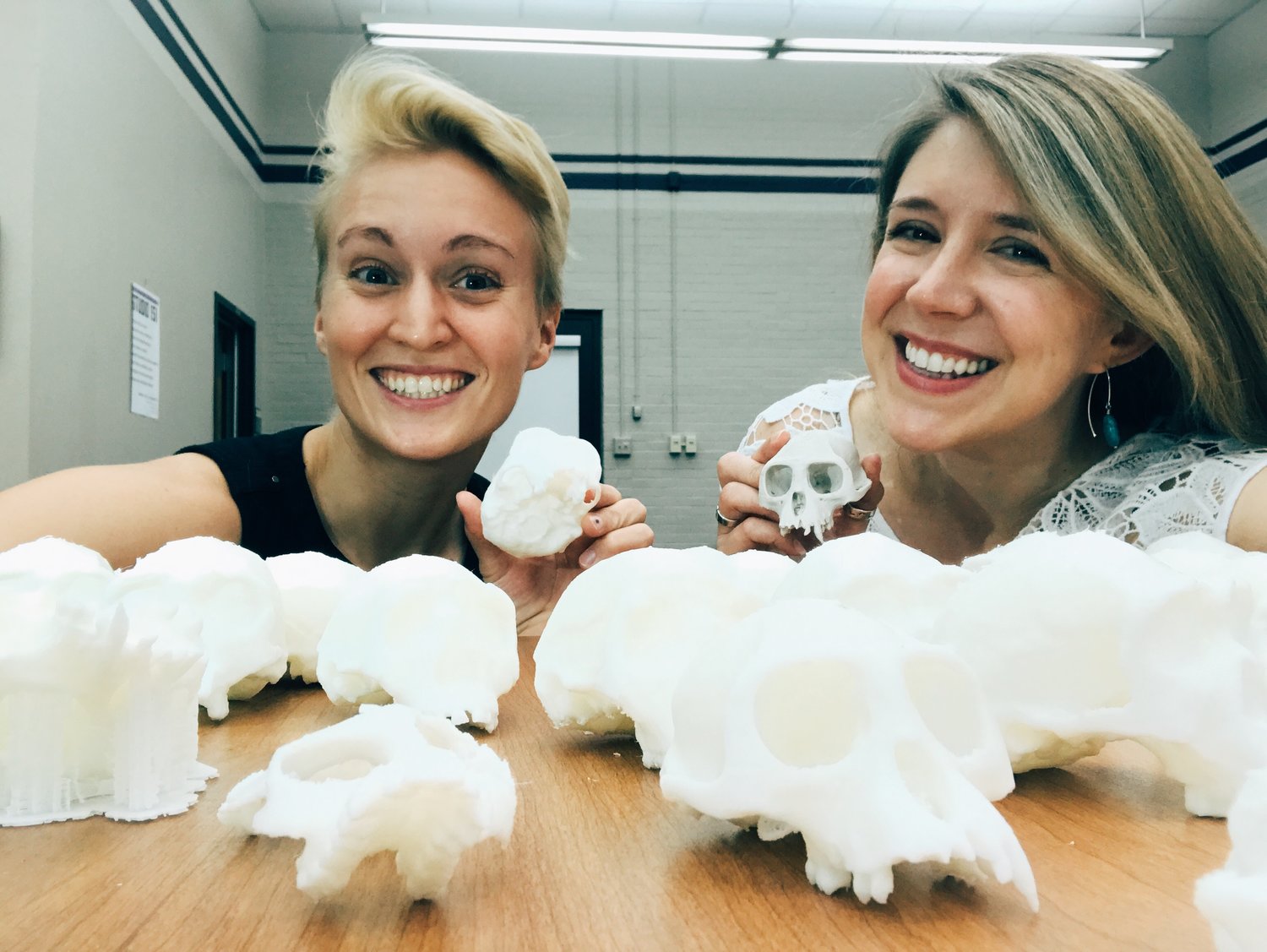

Paige and Becky (pictured) discuss the inspiration behind the project, the results, and the next steps for changing stereotypes of scientists.

Listen to the full episode below, and subscribe to LSU Experimental on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, TuneIn or anywhere you get your podcasts.

Additional Resources

- “Using selfies to challenge public stereotypes of scientists” in PLOS One

- @ScientistSelfies on Instagram

LSU Experimental is a podcast series that shares the research and the “behind the scenes” stories of LSU faculty, student, and alumni investigators across the disciplines. Listen and learn about the exciting topics of study and the individuals posing the questions. Each episode is recorded and produced in CxC Studio 151 on the campus of Louisiana State University, and is supported by LSU Communication across the Curriculum and LSU College of Science. LSU Experimental is hosted by Dr. Becky Carmichael and edited by Kyle Sirovy.

Transcript

Becky Carmichael

[0:01] This is LSU Experimental, where we explore exciting research occurring at Louisiana State University and learn about the individuals posing the question. I'm Becky Carmichael. It's national selfie day and we are marking the occasion Dr. Paige Brown Jarreau to discuss our research project "scientists who selfie". Paige and I, along with Dr. Lance Porter from the Manship school here at Louisiana State University, are joined by Imogene Cancellare from the University of New Hampshire, Dr. Samantha Yammine from the University of Toronto, and Daniel Toker from the University of California, Berkeley to explore the role that science selfies play in addressing problematic stereotypes. The project garnered huge support raising over $10,000 through crowdfunding on Experiment.com. Thank you all who back this study. The hashtag created for our work, #ScientistsWhoSelfie, has over 14,000 occurrences on Instagram and Twitter, forming a dynamic community of scientists, science communicators, and science enthusiasts. To celebrate National Selfie Day, Paige and I discussed the inspiration behind the study, the implications of the findings, and what's happening next.

Hi Paige! How are you today?

Paige Jarreau

[1:22] Good. How are you?

Becky Carmichael

[1:23] I'm great! Happy National selfie day!

Paige Jarreau

[1:26] Yeah, this is awesome. Time for selfies.

Becky Carmichael

[1:29] All the selfies, all the time. And I thought this would be really fun to have a special episode of LSU Experimental where we could chat all about selfies and scientists to selfie in this project that we we started what..? A year and a half ago?

Paige Jarreau

[1:45] Yeah, I think it was a year and a half to two years ago.

Becky Carmichael

[1:48] You and I were co authors along with Lance Porter here at LSU. And Daniel Toker..?

Paige Jarreau

[1:55] Yeah, Daniel Toker at Berkeley.

Becky Carmichael

[1:57] He was at Berkeley. Samantha Yammine from University of Toronto and...

Paige Jarreau

[2:04] Imogene Cancellare from Delaware.

Becky Carmichael

[2:07] We had quite a robust group of co-authors, but then collaborators from many different locations.

Paige Jarreau

[2:16] Yeah, it was really fun. It was a very diverse group of people that we set on the beginning to create that diverse group, that diverse research group, because we wanted many different people influencing this study in terms of how we could change stereotypes through different images of different types of scientists.

Becky Carmichael

[2:39] So yeah, and I would like to say that too. Our co-authors were... Some of them are practicing, you know, really strong science communication across multiple mediums, including Instagram, as well as some of us were maybe a little bit more reserved in how we were using Instagram to share our science. So we had really a kind of a nice diversity, both in backgrounds as well as science communication.

Paige Jarreau

[3:05] Right. Yeah. So we wanted this study to be influenced by both science communication researchers, as well as scientists in other areas and practitioners or people who are doing science communication kind of in the trenches every day. And we wanted all those influences to come together in this study.

Becky Carmichael

[3:22] I wanted to just kind of dive right into what inspired the project. And so I wanted to hear kind of your inspiration, because I feel this was your baby that you brought forth to us and then it just all exploded. So tell me what was some of the inspiration for you to do this kind of project?

Paige Jarreau

[3:39] Yeah, I had always been really interested in how scientists use social media. And for a long time, I studied how scientists use blogs, and why they were interested in blogging and what values they brought to blogging. But I started getting really interested in Instagram personally, because I had discovered this community on Instagram through athletics or sports wellness and things that I was posting to my own Instagram and saw that it grew really quickly. And so I really wanted to conduct a research study with science communication on Instagram. And around that same time, I had seen Dr. Susan Fisk, she's a psychologist, and I saw her present at the Sackler Colloquium on science communication. And I saw her present on this research, she's done showing stereotypes of scientists that were generally perceived as very competent or intelligent and capable of achieving our goals through things like research, but we're not necessarily considered very warm or friendly by the general public. I thought that's so interesting. And I immediately thought of Instagram of this kind of opposing force of selfies of, you know, revealing our lives to people on Instagram. And I thought it'd be really interesting to see if we can change stereotypes through Instagramming about science.

Becky Carmichael

[4:59] And that's what I think is really interesting, this whole idea of how scientists are considered to be not so warm. Because as a scientist, I think that I'm approachable. But if others are trying to come up and talk to me about the work that I've done in the past or work I'm doing now, this really has started getting me to think about what is it that is causing this disconnect where we're not being able to engage with others outside of the sciences. And then also, Instagram just feels like a welcoming place. I really think that the visual side of this, where you can take a peek at a moment captured in time, you don't necessarily have to be able to... I mean the caption is really important. We can talk about that a little bit. But to be able to look at this image and gather this whole idea of what's going on... To me it just seems warm. It seems like inviting.

Paige Jarreau

[5:57] Yeah. I mean I think that some of the problems as scientists, if someone asked us about our work, we automatically jump into that, like scientific language. The only way we know to talk about our work. And I think sometimes maybe the visuals just force us into a different mode of communication, where you don't have that scientific language. So it automatically has to be these more universal concepts of smiling and enthusiasm for your work and the things that might, you know, communicate more warmth.

Becky Carmichael

[6:28] And right there, just the fact that you can be really enthusiastic on a social media platform like Instagram and share your really deep interests and the things that you're discovering in that moment, or in some cases when something has just come completely crashing down. But you can't necessarily share in a traditional scientific paper. Did you see a lot of selfies within the health and wellness arena compared to science when we started.

Paige Jarreau

[7:04] Yeah, that's really interesting question. I think that different areas of science have picked up social media to different extents. Actually, doctors and healthcare professionals are automatically... Well if you look at stereotypes in the general public of scientists versus doctors, doctors and nurses are actually considered more warm than scientists. I think part of the reason is because we see doctors. Average people see their physicians when they go to the doctor's office and they see nurses. So just that familiarity with a group of people who is obviously trying to help them makes those groups seem more warm automatically. And so I think the problem comes with scientists, you know, biologists, physicists, people that we might know them as next door neighbors but we don't know that they're actually... We don't know that they're a physicist or biologist. And so not knowing them, I think makes those stereotypes worse and might be accentuated through the media or what we see on TV. And leads to us having stereotypes about these people because we just don't really know them that well.

Becky Carmichael

[8:11] Yeah, I think that somebody will ask you what is your profession? What do you do? And if you're a doctor, you're a teacher, you're a nurse... That's something that you said, we have interactions. That's obvious, but if someone asks, "what do you do?", and you say, "oh, disturbance ecology". They're like, "What? What is that?" And then it's not as accessible We're not as familiar with those ideas. The other thing that you just mentioned was portrayal by TV. Do you think that some of the portrayals of science and scientists on TV has led to this current stereotype issue?

Paige Jarreau

[8:53] Yeah, I don't know. I think actually, there is research showing, you know, a connection between those two about causal relationships. But it definitely seems the stereotypes that people have today about scientists definitely seem to reflect traditional portrayals in the media. So even though those have gotten better over time, we still see like the mad scientist, or at least a socially awkward scientist when they're presented in TV or on TV shows.

Becky Carmichael

[9:20] I think that's why I'm not a big fan of certain shows. Because I'm like, no, that's not how everyone is now. We're not all just bumping into stuff.

Paige Jarreau

[9:28] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[9:29] I mean, I still have some times I'm awkward anyway in terms of how I have a conversation sometimes. But that's not the generality.

Paige Jarreau

[9:37] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[9:39] And I think cartoons are also a place where for a lot of kids, we still see that mad scientist blowing things up and having different mishaps. I don't think... So it's almost perpetuated at a younger age, as well.

Paige Jarreau

[9:55] Yeah, exactly.

Becky Carmichael

[9:56] I kind of want to dive into a little bit about selfies in general. You and I have both talked about how awkward or how kind of strange it is for us to take selfies. Yeah. And I know that it's something that... I'm trying to capture something. How easy was this for you to take a selfie entering in this study, and have it has it gotten easier for you?

Paige Jarreau

[10:26] It's maybe gotten a little bit easier. I never was great at taking selfies, but in my personal Instagram, I did a lot of setting up the camera and doing... You know I do acrobatics and stuff. And so that found them a bit distant. Setting it up and I just go do my thing. So kind of that self portrait, sure, but not in a way that you're like holding the camera up to your face. I think, you know, really close selfies, sometimes kind of awkward. But if someone's taking a picture of you, or you kind of set up your camera on a tripod and take pictures, I started to get better at that. And so that's kind of the way we conceptualized selfies in our study which we'll talk about a little bit in a little bit, but was actually more like self portraits of scientists. So you don't necessarily have to be obviously holding the camera up to your face, but you can have it on a tripod or set up like a 10 second timer and take a picture of yourself doing something in the lab. And it's a little bit easier, a little bit more distant

Becky Carmichael

[11:30] At the initial part of the study and then even prior, my own idea of a selfie was that it was something that people are doing if they don't have someone else to take the picture or it's a little narcissistic, right?

Paige Jarreau

[11:47] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[11:47] They're just kind of wanting to make sure that their face is all over something. Or someone's making that inevitable duck face.

Paige Jarreau

[11:56] Yes!

Becky Carmichael

[11:58] But the point you're bringing up is how we defined "what is a selfie"? And to really reconsider how you're capturing yourself in that shot, so that someone can see who you are, what you're doing, and get a better sense of what your daily life is.

Paige Jarreau

[12:18] Yeah, I think exactly that. I mean, we can go into talking about stereotypes about this. Probably stereotypes of selfies. Like what a selfie is and like this, you know, cultural phenomenon of selfie sticks. And like you said, People aren't taking pictures of themselves in weird angles. But I mean, historically... I mean, I think since we invented cameras or photography, people have been taking self portraits. It's just how it's done. So I think the modern smartphone that turned the camera around at yourself at first, it was kind of weird. We looked at it a little bit strangely, but I think now there's so many different ways to turn the camera around on yourself that it doesn't have to look like you said, that duck face. Kind of weird angles of just making it all about your yourself and your face.

Becky Carmichael

[13:09] So let's chat a little bit about the study design. So we did a pilot study here at LSU first, with a sample of students. I think I'm getting ahead of myself. So we did the pilot here at LSU. We had a set of Instagram accounts that had curated content, both of images that just had some kind of still with no person within it. Then the same picture with a male and a smiling face, and then a female with a smiling face. Let's talk through a little bit with the listeners, why we have the different types of curated accounts, and then how we found students to start testing out that process.

Paige Jarreau

[14:02] Yeah. We came up with the idea that we wanted to do... We had a lot of ideas of what we wanted to do to test whether we could change stereotypes of scientist warmth. But in the end, as with all experiments, you have to narrow down what exactly you're going to manipulate in an experiment. So you have to be in a very controlled place to change just one small thing that say one group success versus the other so that you can say what really made a difference and whatever your outcome was. And so we decided just to do, very simply, having a human face in the science picture or not. So we actually got real scientists to create these images for us where, let's say they would take a picture of a microscope. And then they would take a picture of themselves with the microscope. And then we ask them to have a colleague of the opposite gender pose in the same way. And so yeah, at first, we created different Instagram accounts, because we wanted to... One of the things that Susan Fisk had an idea of was that, in addition to maybe pictures of scientists that are humanized and that being able to change people's perceptions that scientists are warm, was the idea that diversity also matters. And so it might be seeing... Maybe just one scientist selfie might not make a big difference, but seeing multiple different scientists, a diverse set of scientists, doing the same thing starts to make you question a monolithic stereotype of mad scientists, for example. So we made different Instagram accounts so that we could collect a series of images together. So in this experiment, people would see a bunch of science images posted by scientists, but with no human in the picture, or they would see a bunch of male scientists faces or a bunch of female scientists faces in these images.

Becky Carmichael

[15:51] In all of those images, we had the same caption.

Paige Jarreau

[15:54] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[15:54] So that, if they're reading it, we could see we had some questions too. When we had these viewed about the content that was written as well.

Paige Jarreau

[16:05] Right. So yeah, we could see if having a human face in the picture changed how much people can remember from the captions. But we needed to keep the captions all the same, because that's not what we were most interested in telling differences about.

Becky Carmichael

[16:18] And we had scientists that were beyond Louisiana State University, because the pilot we did here at LSU with LSU students. But we had pulled pictures from multiple universities and locations. So from some of our colleagues as well from the other universities.

Paige Jarreau

[16:39] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[16:41] Which I thought was really interesting to kind of grab and have it have a more robust sampling of images. And then also in case, any of the students that we had looking at them, we're not like, "Oh, I know who this is".

Paige Jarreau

[16:54] Right. Yeah. So for the pilot study, we didn't want to have LSU scientists in case they knew the scientists. That would definitely skew the results, so we went nationwide. Actually, I think we had some international scientists sending us images. So that was probably one of the coolest parts of the project. Working with these scientists to create these image sets. You could tell that the scientists who were involved were super excited. We had, like 20 to 30, scientists create image sets for us.

Becky Carmichael

[17:22] I mean, this particular project, the response of scientists from start to finish has just blown my mind. We had the experiment.com, the crowdfunding project, like immensely supported. Well over what we had initially targeted in terms of what we needed to do the project. But then how the hashtag, #scientistswhoselfie, how that just has blown up along with the following that's on our Instagram scientist selfies. I looked last night, and I'm like, wow. There's well over 6000 people following just this one account, and people are every day still using this hashtag.

Paige Jarreau

[18:17] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[18:18] I just feel like this started something that was necessary and needed. And then it's just been an incredible continuation of involvement.

Paige Jarreau

[18:30] Yeah, it's so fun. That we started this research project, and we started a scientists who selfie hashtag really as a way to raise awareness about our research project. Because, like you said, we were crowdfunding it. Crowdfunding national research, but it took off. And it was obvious that this was something that the science community really needed, I guess, as an outlet to share their work and be okay sharing selfies. It was like really an excuse, I guess, even though there shouldn't really be an excuse to tell our own stories. But as scientists, I think we don't think about that being okay, I guess? I don't know, you know, and so it's really cool to see scientists jumping into this project thinking "this is so cool" and "I can share my selfies as a way to support science research". And so I later have had people, and I'll talk to them about our research project or maybe just introduce myself. And they don't really know me, but then they'll say, "Oh, do you know about", you know, if you ever seen this hashtag scientist who selfie. I go, "Yeah, I know that".

Becky Carmichael

[19:34] Like, "Oh, you created that"

Paige Jarreau

[19:37] Like, it's funny, because they know the hashtag, not us.

Becky Carmichael

[19:39] Well, the thing that I really got excited about was this true authentic representation of all of the different facets of science. Across every single sub, subsection, discipline, there was just there was just such an outpouring, and then also, these very unique perspectives. So not only were we having all these scientists contribute, but then they were inspiring other scientists to look at, "oh, what can I capture in my space?" I love that we had people, obviously, that were in remote parts of the world, sharing some of the organisms that they were studying. I love that we had individuals at a chalkboard and just kind of showing this is how they're doing their work on a daily basis. And then seeing this range of ages that were contributing. So we had older individuals, full faculty, you know, that are sharing what they're doing. But then also, within courses and classes at LSU, the students that are just starting their science journey and starting to become part of that network and community, how they're using this to contribute and get to know others.

Paige Jarreau

[20:52] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[20:53] Yeah, I was... I still am overwhelmed and inspired by what people are sharing.

Paige Jarreau

[20:59] Oh, yeah, sure.

Becky Carmichael

[21:01] That was kind of... (giggling) Okay, so where were we talked about the pilot and then... So what do we do? We did the pilot here. We got some results, and then we launched this nationally, right?

Paige Jarreau

[21:19] Yeah, so we got some really positive findings from a lab experiment where we actually had students looking at iPads, and let them browse through these Instagram accounts. And some of the students like... We set some privacy settings. Some of them got around that and started browsing some other accounts that weren't part of the actual study. But actually, it was good, because we saw even with what... It essentially watered down the stimulus of having students look at these scientists' selfies or the scientists' Instagram accounts. We still saw some pretty positive findings. So we decided to essentially do the same experiment, but in a much bigger sample. So we went to a company called Qualtrics that basically helps you do online surveys, and they recruited a US representative sample of several thousand participants for us. And so essentially, we did the same thing in an online survey. So people would take the survey, and as part of it, randomly they would see either an image that was just science or a female scientist selfie or male scientist selfie. After browsing through the content, they would ask them questions about their perceptions of scientists, of these scientists in particular, as well as scientists in general, and questions about their stereotypes of science and scientists.

Becky Carmichael

[22:47] And so let's talk a little bit about then the findings. So one of the findings was that scientists who were posting selfies on Instagram were perceived to be warmer. I want to talk just a little bit about how we were measuring warmth.

Paige Jarreau

[23:02] Yeah. So we took Susan Fisk's kind of model of stereotypes, and essentially asked a series of questions that get at warmth, or competence. And so it's kind of like asking people about a series of words and how well these words describe a particular individual or group of individuals. So like, for example, in measuring stereotypes of scientists, we ask you in general, do you think scientists are, friendly, sociable, warm, competent, and so you ask a series of negative words in there as well as positive words. And at the end, you pool together these different questions into a scale that measures competence or warmth.

Becky Carmichael

[23:53] And what we found was that, yes, this was really helping with the perceived warmth, right?

Paige Jarreau

[23:58] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[23:59] And that's pretty major. I mean, I know this was kind of the first study. The first initial kind of study on what selfies were doing and trying to get toward this stereotype. So let's chat a little bit about what does this mean? So if this is showing that it helps increase and improve how scientists are perceived as warm, that really gets toward potentially those problematic stereotypes that have persisted for so many years.

Paige Jarreau

[24:31] Right. So I guess we have to step back and just point out that in this model of how much we trust someone, warmth is actually primary. So how warm and friendly you find someone says a lot more about how much you trust them, and what they have to say, than your perceptions of how competent they are. Because a scientist can be very intelligent, but maybe have nefarious goals or motivations. And so the finding that in these Instagram accounts, when people saw selfies of scientists, not just images that the scientists had obviously posted to Instagram with little stories and captions. They saw these scientists who had selfied to be much warmer, as well as just as competent as individuals who had seen just science only images.

Becky Carmichael

[25:23] Okay, so with with these findings, but kind of knowing that perceived warmth, with trust... Paige, what are some of the implications of the findings that you really see and you're really excited about?

Paige Jarreau

[25:35] Yeah, so I think that one of the major problems is that scientists are increasingly entering the public arena, where they have things to say on public issues, serious issues. From health issues to climate change. And when scientists become science communicators, how much we trust them and what they have to say matters much more than, let's say historically, when we were maybe getting that news passed down to us through our communities or the news media. And so how much we trust scientists and how warm that we perceive them to be has real implications for whether we listen to them when they tell us things about health behaviors that we should or shouldn't be doing, or what's happening in our backyard as far as climate change. So I think that it really matters down to a personal level for people of what science they're going to listen to, and what they might not based on the person who's communicating to them.

Becky Carmichael

[26:39] I also think this touches on how we are preparing our scientists and a scientist herself to really engage in the communication piece. And I know we've talked about this before, that there are people that are trained specifically as science communicators. I know I personally think that as you're becoming a scientist, you're entering into that that trajectory. You should also be simultaneously training on how to communicate to multiple audiences for multiple reasons. And obviously, to share your outcome of your work. How do you see this role evolving? Do you see it still, as a science communicator and scientists? Do you see something merged? What is your take? Because I mean, obviously, I think people see it as an important skill.

Paige Jarreau

[27:34] Yeah, I think it's more and more merging where scientists have to act as communicators. Whether it's for their own research or getting into larger issues. So I think it definitely seems like that role is blending together, where as a scientist, you do need to learn to communicate. And part of that is learning to relate to your audience and helping them relate to you, which ideally means establishing not just your competence, but also your warmth with people. And then you have shared values with them. Because if you go and talk at a scientific conference, I mean, you might start with some chit chat and talking about things that you've all experienced at this conference together. And you know, you establish some amount of relatability, you might not just go up there and start listing off your credentials, because you want to establish some rapport with the audience first.

Becky Carmichael

[28:28] You want to establish that you're a person.

That you actually know how to be a person, and it's not just all of the degrees and

your achievements. I completely agree with that. I think that there's something about

connecting with somebody at a personal level or on a particular issue that then opens

up the channels for you to have a conversation. I think that people can be more empathetic

with each other, and they can start to actually learn from each other and start to

have that dialogue, especially on these tough issues. Like what are we going to do

regarding climate change? How are we going to address different issues of pollution

and other pieces that we're facing?

Paige Jarreau

[28:29] Right!

Right. I kind of think of it like, the problem with online, if we're talking about

online communications is that for most people, they might see a scientist quoted in

a news article or see a scientist appear on TV. But it's such a little exposure, that

if they already have that stereotype in mind that that scientist is kind of cold or

not necessarily very warm and relatable, there's nothing there to establish that trust.

It's such a way that they will listen to what that scientist has to say. I think that's

where these selfies and scientists engaging on Instagram comes into play. Exposing

people to scientists in a way that they see them as someone like me who might share

my values and I think is friendly?

Becky Carmichael

[29:55] Oh yeah, just the humanization. That face, right? And seeing a face... Seeing, I guess... Kind of getting into like a little bit of the captions. What are they using to describe? What are they visually using to describe the situation in that moment, but then what other information are they providing us so that we can really kind of get into and enjoy them in that space and understand it?

Paige Jarreau

[29:58] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[30:18] So for those that want to start contributing more, or those that are already contributing, let's talk about some tips we would give people for capturing a really good selfie or self portrait.

Paige Jarreau

[30:33] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[30:34] So I personally, one of the things that I like to think about is what's in the background? So thinking about what is it exactly that I want to share? And then making sure that I frame that up. And I don't have some kind of random thing that happened. And then that steals the attention.

Paige Jarreau

[30:52] Yeah, I think it goes back to that storytelling, or, you know, telling the story and bringing someone with you on the science journey. They can relate to that. So they might not relate to, you know, the equations or models you're running on a computer, but they can relate to having a goal and achieving something hard and overcoming difficulties in doing that. And I think sharing the story of our science and visually being really excited at a result that just came out to taking a selfie of that within the science lab, and then explaining it in the caption. I mean, that's something that... You all might not have ever seen cells in a petri dish before, personally, but they can relate to this story of discovery, maybe.

Becky Carmichael

[31:09] On that emotion that's captured in either the facial expression, gestures, things like that.

Paige Jarreau

[31:45] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[31:47] What's another tip that we could share with someone?

Paige Jarreau

[31:51] So I think, certainly one of the things from our study, was just smiling and making eye contact. And I think that part of the selfie is that establishing rapport with the person who's is looking at this means making eye contact, smiling, expressing emotion, versus being an emotionless robot doing something.

Becky Carmichael

[32:11] I don't think that that's really going to help the stereotype. Looking at the balance of like 80%, at least, being the science related and maybe 20% or less being more personal kinds of things. I think there's a nice balance between showing that you're not always somebody that's just stuck in the lab, but that you actually have a life and it can be rich. And then even finding the science types of things in your everyday life. I think that that's a powerful piece that kind of shows that someone else can interact with that situation, not just in a lab setting or a field setting.

Paige Jarreau

[32:57] Yeah, I think that certainly if you have a Instagram account, and your science isn't... We're not saying that every picture needs to be a selfie, and that might actually take away from telling the story about science. But the inserting of some selfies in there, especially in a way that brings people on a journey with you, like brings them into the moment that you found a little frog on the ground ends up being a new species, or whatever the experience is. If you can bring them to that moment through a selfie, I think that's really powerful.

Becky Carmichael

[33:32] And we've got some examples of that. Where someone has either held something up, or they've included either an organism or some kind of instrument close to their face. But then on the second picture or subsequent pictures, then they're showing you like either the steps or they're showing the landscape, or they're giving you more detail about what it was.

Paige Jarreau

[33:51] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[33:52] So I know being the ecologist, the pictures that really grab me are most the time related to some kind of field setting. I just get really excited when I get to see some kind of new organism or landscape because I'm not getting into the field anytime soon, right now. What are some of the pictures that really resonate with you and get you excited?

Paige Jarreau

[34:12] Yeah, I loved seeing people share their selfies on social media through the scientists who selfie hashtag, because I love seeing those selfies of things I could never imagine seeing in person...

Becky Carmichael

[34:26] Yeah!

Paige Jarreau

[34:27] Like an image inside of LIGO or with some crazy piece of equipment and the scientists are out there taking a selfie. Or showing the magnitude of how huge this instrument is. Or how tiny this little frog is and what it's like to have a mosquito lab and have to feed the mosquitoes yourself with your arm. I mean...

Becky Carmichael

[34:48] That still makes me itch.

Paige Jarreau

[34:48] Like showing those selfies that really show what science actually is like and ways to break down this... I don't know. We tend to think of science as maybe it's kind of dry, or it's so methodological that it's almost boring, but there's so many cool and crazy aspects of doing science. I love to see selfies that communicate that.

Becky Carmichael

[35:12] I also like to see some of the mishaps, right? I really relate hard when something is going completely awry, and someone has taken the moment. They've captured it. They've left that emotion there to show that it's just real.

Paige Jarreau

[35:26] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[35:26] Things break down or don't cooperate and to capture that as well has been something I have... To say I enjoyed it is not the right word. It's more I've appreciated that someone has been that raw and open about those situations.

Paige Jarreau

[35:41] Right.

Becky Carmichael

[35:42] They are usually really hard. And it can make you pretty upset, but to have someone be able to share that too. To say, hey, you're not alone. We had this happen too. What do you think is next? What would you like to do next?

Paige Jarreau

[35:56] We have so many things we can follow up with the scientists who selfie. I was really interested in the beginning of interaction with scientists and how that can impact stereotypes. Because it's awesome to see an image, but what if you could talk to that scientists through comments on an Instagram image, and they reply back? What does that interaction with the scientists really do? And I'm assuming that even much more powerful than seeing images or portrayals of scientists, is being able to interact with them online. So it gets a bit complicated to study, but I would love to look at that. How interaction with scientists online changes stereotypes, maybe more long term.

Becky Carmichael

[36:40] Personally, I'm still interested in students. So I know that there's some things that have been done with draw your science. And I'm also interested in how it influences science identity, especially with incoming students in higher education. And what that does to help them kind of learn more about themselves. Learn more about where they fit into science. What is science for them? As well as them trying to follow that peace. How does this help them also become part of the community and learn ways in which to communicate like the particular scientists they're aspiring to join in a future date?

Paige Jarreau

[37:21] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[37:22] That'd be kind of fun.

Paige Jarreau

[37:23] Yeah, I'm also really curious. I think that we'd be remiss to not talk about the fact that our study found certain findings but among people that weren't scientists. So for the public, or people that aren't scientists, seeing scientists take selfies and be humanized increases their perceptions of the scientists being trustworthy. But we got a lot of questions from the science community after our study asking what about other scientists? Like if I take a selfie in the lab, do other scientists, do my colleagues, and my potential professors or future job employers? Will they actually see me as less serious of a scientist?

Becky Carmichael

[38:01] Yeah.

Paige Jarreau

[38:02] And that is a real possibility, unfortunately. I hope that's changing and there's like a sea of change of the culture in science changing towards more openness and more science communication friendly environments. But I'd love to do a study on that. To see how other scientists perceive scientists who selfie.

Becky Carmichael

[38:20] That would, I think, be really interesting and would be timely, because I do think that there's always going to be that constant push of "what are you doing?" and "are you doing enough?" And is this type of interaction considered an other? Or is it going to be considered part of the communication package?

Paige Jarreau

[38:39] Yeah.

Becky Carmichael

[38:40] How you're really talking about and sharing your results. I do think there's a sea of change, and I think that people are starting to see. But I think that it would be an interesting study to see how much of that is changing.

Paige Jarreau

[38:53] Yeah, for sure.

Becky Carmichael

[38:56] Paige! Thanks so much for coming in today and yeah! Happy National selfie day!

Paige Jarreau

[39:01] You too!

Becky Carmichael

[39:03] This episode of LSU Experimental was recorded and produced in CXC Studio 151 here on the campus of Louisiana State University, and is supported by LSU's communication across the curriculum and the College of Science. Today's interview was conducted and produced by me, Becky Carmichael. Our theme music is "Brambi at Full Gallop" by PC3. To learn more about today's episode, ask questions, and recommend future investigators, visit cxc.lsu.edu/experimental. While you're there, subscribe to the podcast. We're available on SoundCloud, iTunes, Stitcher, and Google Play.