Lingerie Redefined: Iconic Yet Overlooked Everyday Fashions 1900s - 1920s

Exhibition Dates: January 2016 - Fall 2017

Lingerie Redefined: Iconic Yet Overlooked Everyday Fashions 1900s-1920s focuses on day dresses, lavishly embellished and white in color similar to fashionable undergarments of the period. Referred to by costume historians as a "lingerie dress," this garment type is found in period American retail advertisements and mail-order catalogs employing terms such as "garden party dress," "summer dress," "graduation dress," "afternoon frock," and "dancing frock," which illustrate its broad use for multiple events. Although the dress was widely available, the term "lingerie dress" is seldom used in period marketing to refer to it.

The lingerie dress can be traced through three distinct periods that surround World War I: Pre-War (1900-1913), Wartime (1914-1918), and Post-War(1919-1929). Its evolution within the greater period was influenced by Parisian couturiers, changes in women's societal roles, wartime restrictions, and the relaxation of proper strict Victorian social conventions.

In its initial and most significant period prior to the war, the lingerie dress restricted the body and featured extensive ruffles, lace, and embroidery on finely-woven cotton and linen textiles. During Wartime, the dress was simpler in silhouette and constructed using semi-transparent voile and net fabrics often decorated with subdued surface embellishment. By the Post-War years, the changes in women's lives initiated during the war paralleled the emergence of a garment as liberating as the social and political changes had been.

At the height of its popularity, the lingerie dress was an instrumental piece in a woman's everyday wardrobe. Although seldom mentioned in costume history books, its significance in early 20th-century everyday fashion is not to be overlooked.

Pre-War Fashion: 1900-1913

Prior to World War I, Paris was the major source for fashionable clothing, exerting substantial influence on what was available in the American marketplace. Fashion consumers demanded exact reproductions of French couture gowns[i] – some visiting Paris twice a year to purchase clothing[ii] while others shopped retail stores and local catalogs that copied French fashions.

From 1900 to 1909, the mature female silhouette and the profusion of decorative details in women’s dress was considered the epitome of femininity. The “S”-shaped “hourglass” silhouette dominated fashion and was one in which the female’s upper body appeared to be pushed forward with her hips pushed backward. This desired look was achieved through the use of restrictive corsetry worn underneath garments designed with close-fitting high-necked collars, “pouter pigeon” “mono-bosom” bodice fronts, and hip-hugging skirts. Illustrator Charles Dana Gibson’s fictitious character, the “Gibson Girl,” popularized the silhouette and became the icon of American female beauty during the period. Known as La Belle Époque or “the beautiful age,” the years were marked by societal lavishness and ostentation in all aspects of life, demonstrated in fashion by the use of excessive ornamentation, frills, and trim in dress. It was a time of great wealth for the upper-echelon of society[iii] but also a time when upward mobility was possible for the lower classes. As a result, the emulation of fashionable dress’s richness and impracticality could be used to reflect one’s new or rising social status.

By 1910, women’s fashion began to be impacted by Parisian designers such as Paul Poiret, the Russo-Japanese War, and the costumes of the Ballets Russes, a Russian ballet company that first appeared on the Parisian stage the year before. These influences resulted in a preference for dramatic bold garment colors, Oriental-inspired clothing, and the “hobble” skirt (so close-fitting at the lower leg that the wearer was forced to walk with small steps). After Poiret reintroduced the empire waist – one placed above the natural waistline – the fashionable silhouette became more linear with corsets designed to smooth out the hips rather than constrict the waist as those used to achieve the hourglass silhouette. Falling straight from the waist to the floor, skirts were first columnar before becoming very slim and tapering to the ankles. While hobble skirts were worn primarily by fashion followers, most women’s skirts also followed the slimmer silhouette but incorporated a slit or godet added at the hemline for ease of walking.[iv]

Lingerie and Lingerie Dresses

“Of the many other changes that were taking place [in fashion], none was more dramatic [at the turn of the century] than that connected with lingerie.”[v]

Although the term “lingerie” was first introduced into the American vocabulary in 1852 by Sarah Josepha Hale (editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book magazine),[vi] widespread interest in fashionable undergarments did not occur until the turn of the twentieth century as more sophisticated and highly-evolved decorative techniques[vii] on lighter, softer materials[viii] became available. The “lingerie dress” derived its name from the lavish adornments found on undergarments of the period. Its popularity was supported by the Belle Époque’s societal preference for excessive ornamentation. Embellishments included lace insertion, lace trim, tucks, embroidery, ruffles, ribbons, and bows applied to base fabrics such as fine linen, as well as cotton batiste and lawn. The gowns were worn for special daytime occasions, primarily in the summer.[ix]

Catalogs offered selections to the middle and lower classes who did not have sewing skills or could not afford a dressmaker.[x] As the American ready-to-wear industry grew, companies such as Sears, Roebuck, & Company and B. Altman & Company offered ready-made versions in their catalogs. Others, such as Marshall Field of Chicago, employed dressmakers to reproduce advertised garments upon placement of orders.[xi] Women’s apparel, including the lingerie dress, was also sold in retail stores that offered semi-finished pieces to be altered to fit an individual woman on site.[xii]

Tub Dresses

First appearing in fashion catalogs and advertisements in the early 1910s, decorative “tub dresses” included details similar to those of the lingerie dress. The garments were made of washable fabrics and ranged from simple styles to those that incorporated some decorative elements such as embroidery and machine-made flat-surfaced shadow lace.[xiii] Originally worn as morning dress, tub dresses were considered appropriate attire for more formal lunches and afternoon events such as tea, thus serving as evidence of a relaxation of turn-of-the-century American social formalities.

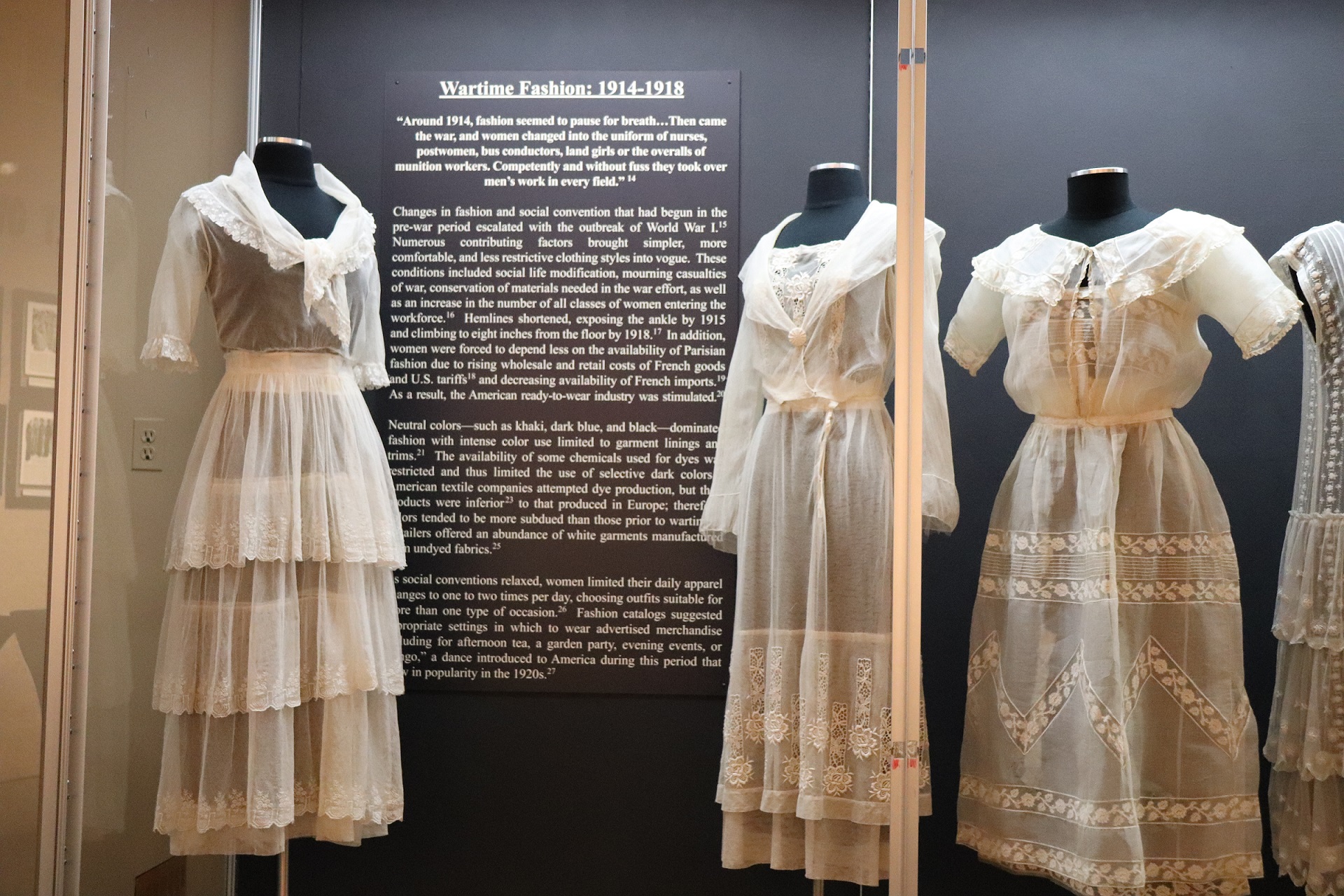

Wartime Fashion: 1914-1918

“Around 1914, fashion seemed to pause for breath…Then came the war, and women changed into the uniform of nurses, postwomen, bus conductors, land girls or the overalls of munition workers. Competently and without fuss they took over men’s work in every field.”[xiv]

Changes in fashion and social convention that had begun in the pre-war period escalated with the outbreak of World War I.[xv] Numerous contributing factors brought simpler, more comfortable, and less restrictive clothing styles into vogue. These conditions included social life modification, mourning casualties of war, conservation of materials needed in the war effort, as well as an increase in the number of all classes of women entering the workforce.[xvi] Hemlines shortened, exposing the ankle by 1915 and climbing to eight inches from the floor by 1918.[xvii] In addition, women were forced to depend less on the availability of Parisian fashion due to rising wholesale and retail costs of French goods and U.S. tariffs[xviii] and decreasing availability of French fashion imports.[xix] As a result, the American ready-to-wear industry was stimulated.[xx]

Neutral colors, such as khaki, dark blue, and black, dominated fashion with intense color use limited to garment linings and trim.[xxi] The availability of some chemicals used for dyes was restricted and thus limited the use of selective dark colors.[xxii] American textile companies attempted dye production, but their products were inferior[xxiii] to that produced in Europe; therefore, colors tended to be more subdued than those prior to wartime.[xxiv] Retailers offered an abundance of white garments manufactured from undyed fabrics.[xxv]

As social conventions relaxed, women limited their daily apparel changes to one to two times per day, choosing outfits suitable for more than one type of occasion.[xxvi] Fashion catalogs suggested appropriate settings in which to wear advertised merchandise including for afternoon tea, a garden party, evening events, or “tango,” a dance introduced to America during this period that grew in popularity in the 1920s.[xxvii]

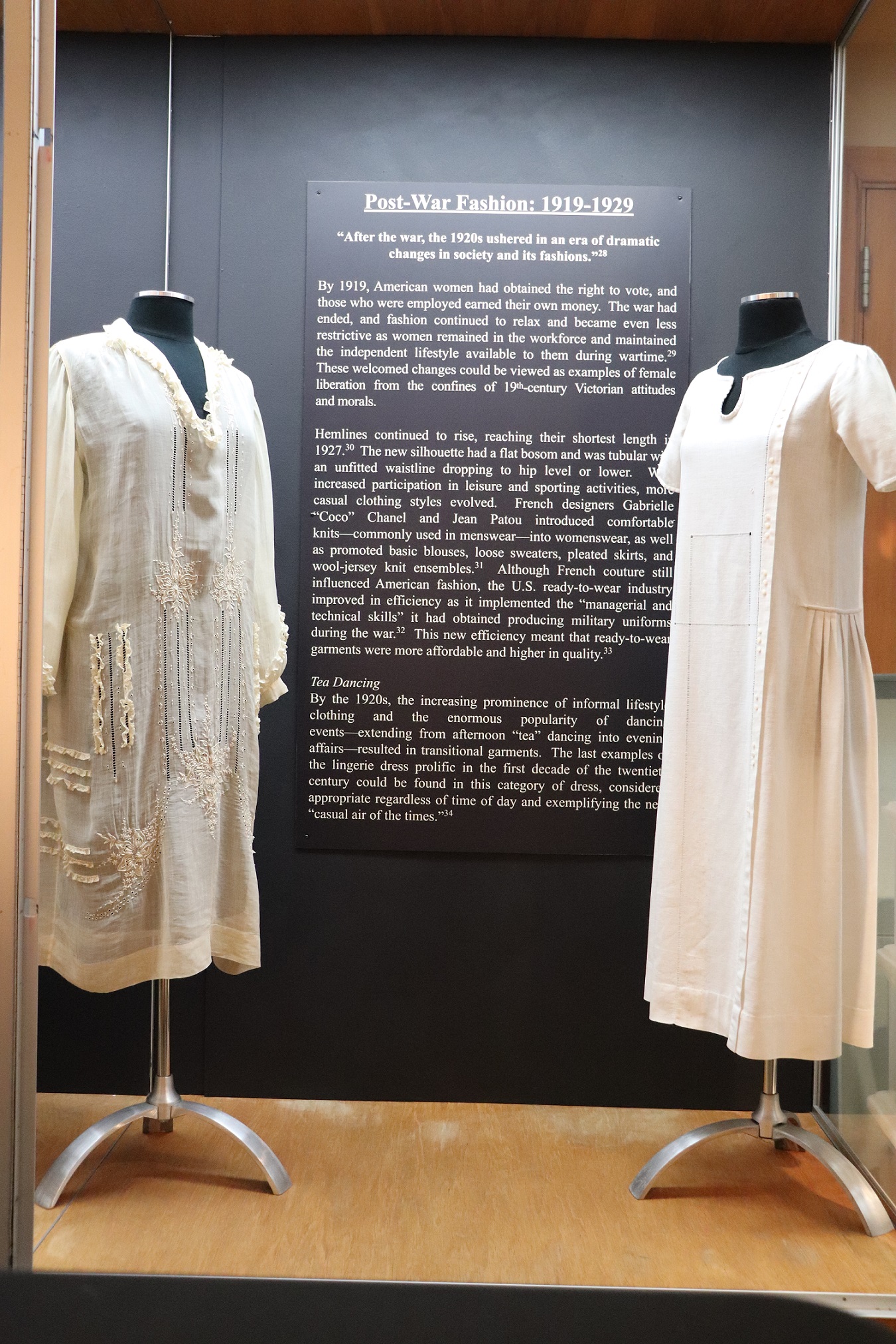

Post-War Fashion: 1919-1929

“After the war, the 1920s ushered in an era of dramatic changes in society and its fashions.”[xxviii]

By 1919, American women had obtained the right to vote, and those who were employed earned their own money. The war had ended, and fashion continued to relax and became even less restrictive as women remained in the workforce and maintained the independent lifestyle available to them during wartime.[xxix] These welcomed changes could be viewed as examples of female liberation from the confines of 19th-century Victorian attitudes and morals.

Hemlines continued to rise, reaching their shortest length in 1927.[xxx] The new silhouette had a flat bosom and was tubular with an unfitted waistline dropping to hip level or lower. With increased participation in leisure and sporting activities, more casual clothing styles evolved. French designers Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and Jean Patou introduced comfortable knits—commonly used in menswear—into womenswear, as well as promoted basic blouses, loose sweaters, pleated skirts, and wool-jersey knit ensembles.[xxxi] Although French couture still influenced American fashion, the U.S. ready-to-wear industry improved in efficiency as it implemented the “managerial and technical skills” it had obtained, producing military uniforms during the war.[xxxii] This new efficiency meant that ready-to-wear garments were more affordable and higher in quality.[xxxiii]

Tea Dancing

By the 1920s, the increasing prominence of informal lifestyle clothing and the enormous popularity of dancing events—extending from afternoon “tea” dancing into evening affairs—resulted in transitional garments. The last examples of the lingerie dress prolific in the first decade of the 20th century could be found in this category of dress, considered appropriate regardless of time of day and exemplifying the new “casual air of the times.”[xxxiv]

Undergarments: 1900-1929

Pre-war and Wartime undergarments and accessories

As the war approached, “Society tottered through the last of the pre-War parties, waved tiny lace handkerchiefs, and carried elaborate parasols until the War came in with its sweeping changes.” ~ Lucille, Lady Duff-Gordon, British couturier in her memoirs Discretions and Indiscretions (1932)

Post-war undergarments.

Post-war undergarments.

Credits

Pamela P. Vinci, Exhibition Curator

Dr. Dina Smith-Glaviana, Guest Curator

References

[i] Gold, A. L. (1991). 90 years of fashion. New York, NY: Fairchild Fashion Group.

[ii] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, Inc.

[iii] Mo, C. L. (2000). To have and to hold: 135 years of wedding fashions. Charlotte, NC: Mint Museum of Art.

[iv] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[v] Robinson, J. (1976). The golden age of style (p. 100). London, UK: Orbis Publishing

Ltd.

[vi] Presley, A. B. (2014). Sarah Josepha Hale: Unwitting influence of fashion? In

Costume Society of America (Ed.), Holidays, Family Gatherings and Celebrations: Annual

Meeting and Symposium of the Southeastern Region of the Costume Society of America.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting and Symposium of the Southeastern Region of

the Costume Society of America, Nashville, TN, November 21 - 23, 2014. Columbus,

GA: Costume Society of America.

[vii] Martin, R. H., & Koda, H. (1993). Infra-apparel. New York, NY: The Metropolitan

Museum of Art.

[viii] Carter, A. (1992). Underwear: The fashion history. New York, NY: Drama Book

Publishers.

[ix] Milbank, C. R. (1989). New York fashion: The evolution of American style. New

York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

[x] Ley, S. (1975). Fashion for everyone: The story of ready-to-wear, 1870’s – 1970’s.

New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[xi] Ley, S. (1975). Fashion for everyone: The story of ready-to-wear, 1870’s – 1970’s.

New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[xii] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[xiii] Calasibetta, C. M. (1988). Fairchild’s dictionary of fashion (2nd Ed.). New

York, NY: Fairchild Publications; Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century

fashion. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, Inc.

[xiv] Contini, M. (1977). 5000 years of fashion (p. 139). Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell

Books, Inc.

[xv] Smithsonian. (2012). Fashion: The definitive history of costume and style. New

York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing.

[xvi] Boucher, F. (1967). 20,000 years of fashion: The history of costume and personal

adornment. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

[xvii] O’Donnol, S. M. (1982). American costume, 1915 – 1970: A source book for the

stage costumer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

[xviii] Marketti, S. B., & Parsons, J. L. (2007). American fashions for American women:

Early twentieth century efforts to develop an American fashion identity. Dress, 34,

79-95.

[xix] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[xx] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[xxi] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[xxii] Tortora, P. G., & Eubank, K. (2010). Survey of historic costume (5th Ed.).

New York, NY: Fairchild Books.

[xxiii] O’Donnol, S. M. (1982). American costume, 1915 – 1970: A source book for the

stage costumer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

[xxiv] O’Donnol, S. M. (1982). American costume, 1915 – 1970: A source book for the

stage costumer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

[xxv] Field, J. (2001). Dyes, chemistry and clothing: The influence of World War I

on fabrics, fashion and silk. Dress, 28, 77-91.

[xxvi] Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th century fashion. New York, NY: Viking

Penguin, Inc.

[xxvii] Gimbel Brothers. (1994). Gimbel’s illustrated 1915 fashion catalog. Mineola,

NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

[xxviii] Mo, C. L. (2000). To have and to hold: 135 years of wedding fashions (p.

42). Charlotte, NC: Mint Museum of Art.

[xxix] Smithsonian. (2012). Fashion: The definitive history of costume and style.

New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing.

[xxx] Smithsonian. (2012). Fashion: The definitive history of costume and style. New

York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing.

[xxxi] Smithsonian. (2012). Fashion: The definitive history of costume and style.

New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing.

[xxxii] Robinson, J. (1976). The golden age of style (p. 12). London, UK: Orbis Publishing

Ltd.

[xxxiii] Van Cleave, K. (2005). “A style all her own”: Fashion, clothing practices,

and female community at Smith College, 1920 – 1929. Dress, 32, 56-65.

[xxxiv] Milbank, C. R. (1989). New York fashion: The evolution of American style (p.

70). New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.; Mulvagh, J. (1988). Vogue: History of 20th

century fashion. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, Inc.